Backstory

Criado-Perez discovered that Twitter did not have adequate protection or processes in place to deal with such abuse and campaigned for change. Twitter reacted and introduced a single-click button to report abuse. Despite being targeted with sustained abuse from over 80 Twitter accounts there followed only two arrests in July last year.

Twitter abuse and the law

Twitter abuse was already on the radar in 2012 when Director of Public Prosecutions, Keir Starmer, announced there needed to be a ‘legal rethink’ on twitter abuse and the boundaries of free speech. His remarks followed abuse received by Olympic diver Tom Daley.

While no prosecution followed the Daley incident, Starmer told BBC Radio 4’s PM programme that social media raised difficult issues of principle for police, prosecutors and the courts. He said that “the time has come for an informed debate about the boundaries of free speech in the age of social media”.

In June 2013 Starmer’s office published final guidelines for prosecutions involving social media communications. These included:

Here the General Principles provide a first hurdle in that they set out (para 6):

As far as the evidential stage is concerned, a prosecutor must be satisfied that there is sufficient evidence to provide a realistic prospect of conviction. This means that an objective, impartial and reasonable jury (or bench of magistrates or judge sitting alone), properly directed and acting in accordance with the law, is more likely than not to convict. It is an objective test based upon the prosecutor's assessment of the evidence (including any information that he or she has about the defence).

But concerningly for victims go on to say at para 7 that:

A case which does not pass the evidential stage must not proceed, no matter how serious or sensitive it may be

Even if the evidential stage is satisfied one then gets to para 8 that adds:

It has never been the rule that a prosecution will automatically take place once the evidential stage is satisfied. In every case where there is sufficient evidence to justify a prosecution, prosecutors must go on to consider whether a prosecution is required in the public interest.

In terms of assessing the offence, the guidelines set out that:

COMMENT & ISSUE

If all the evidential hurdles are overcome, the assessment concludes there is a case to answer AND the DPP decides the public interest test is also satisfied, then this will still be a prosecution under section 127 of the Communications Act 2003 rather than under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997. It is here that confusion is caused not just for victims, who perceive the abuse they endure very much as harassment but also generally. While evidence of harassment within the meaning of the Protection from Harassment Act forms part of the evidential assessment of whether an offence has been committed under the Communications Act, it seems that when it comes to online abuse, the legal process prefers to prosecute this as a communications crime rather than a personal one. That is to say the offence under the Communications Act uses evidence of personal attack to establish that communications channels (such as Twitter) have been abused, or in terms of the Malicious Communications Act, that communications have been malicious.

It was not until Criado-Perez used the media (through a story suggesting police had lost evidence) to apply pressure on the police that the justice process seemed to pick up. Although when Isabella Sorley from Newcastle and John Nimmo from South Shields who appeared in court today were finally charged on the 16 December last year, it appeared that Criado-Perez found out through the press rather than from the CPS - she commented at the time: "Well that's pretty awesome. CPS informing press about charges ahead of me. About the level of victim-support I've grown to expect."

Today's guilty pleas

Pleading guilty at Westminster Magistrates' Court today, it appeared that Sorley's defence was that she was 'off her face' while Nimmo was 'a recluse'. What is troubling is the level of depravity and threat of violence people, of which the two in court today are capable of. In the eyes of victims like Criado-Perez, or indeed Stella Creasy, there can be little excuse or comfort from the fact that bored, wasted loners fill their time by abusing people. What is even more troubling is that Sorely and Nimmo are but two and as Criado-Perez commented on BBC Radio 4's Today programme: "This is a small drop in the ocean, not just in terms of the amount of abuse that I was sent, where way more people than just two were involved, but also women in general, the amount of abuse that they get online and how few people see any form of justice."

Twitter abuse and the law

Twitter abuse was already on the radar in 2012 when Director of Public Prosecutions, Keir Starmer, announced there needed to be a ‘legal rethink’ on twitter abuse and the boundaries of free speech. His remarks followed abuse received by Olympic diver Tom Daley.

While no prosecution followed the Daley incident, Starmer told BBC Radio 4’s PM programme that social media raised difficult issues of principle for police, prosecutors and the courts. He said that “the time has come for an informed debate about the boundaries of free speech in the age of social media”.

In June 2013 Starmer’s office published final guidelines for prosecutions involving social media communications. These included:

- Greater detail about communications targeting specific individuals, particularly making it clear that this category relates to communications that constitute harassment or stalking

- Clarification that where a communication might constitute a credible threat of violence or harassment or stalking, prosecutors should consider whether the offence is racially or religiously aggravated or whether there is aggravation related to disability, sexual orientation or transgender identity and pay particular regard to the increase in sentence provisions

- In those cases where communications might be considered grossly offensive, indecent, obscene or false that meet the high threshold for prosecution, the guidelines have been amended to make clear that prosecutors should particularly consider whether there is a hate crime element to the communication, when assessing the impact on the victim

- Clarification of the wording of the public interest factors to be considered for prosecution under section 1 of the Malicious Communications 1988 or section 127 of the Communications Act 2003

- Clarification that when considering the public interest factors set out in the guidelines in relation to cases considered grossly offensive, indecent, obscene or false, prosecutors should also consider the public interest test set out in the Code for Crown Prosecutors, particularly with regard to the circumstances of and harm caused to the victim.

Here the General Principles provide a first hurdle in that they set out (para 6):

As far as the evidential stage is concerned, a prosecutor must be satisfied that there is sufficient evidence to provide a realistic prospect of conviction. This means that an objective, impartial and reasonable jury (or bench of magistrates or judge sitting alone), properly directed and acting in accordance with the law, is more likely than not to convict. It is an objective test based upon the prosecutor's assessment of the evidence (including any information that he or she has about the defence).

But concerningly for victims go on to say at para 7 that:

A case which does not pass the evidential stage must not proceed, no matter how serious or sensitive it may be

Even if the evidential stage is satisfied one then gets to para 8 that adds:

It has never been the rule that a prosecution will automatically take place once the evidential stage is satisfied. In every case where there is sufficient evidence to justify a prosecution, prosecutors must go on to consider whether a prosecution is required in the public interest.

In terms of assessing the offence, the guidelines set out that:

- Communications which may constitute credible threats of violence to the person or damage to property.

- Communications which specifically target an individual or individuals and which may constitute harassment or stalking within the meaning of the Protection from Harassment Act 1997.

- Communications which may amount to a breach of a court order. This can include offences under the Contempt of Court Act 1981, section 5 of the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 1992, breaches of a restraining order or breaches of bail. Cases where there has been an offence alleged to have been committed under the Contempt of Court Act 1981 or section 5 of the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 1992 should be referred to the Attorney General and via the Principal Legal Advisor's team where necessary.

- Communications which do not fall into any of the categories above and fall to be considered separately (see below): i.e. those which may be considered grossly offensive, indecent, obscene or false.

COMMENT & ISSUE

If all the evidential hurdles are overcome, the assessment concludes there is a case to answer AND the DPP decides the public interest test is also satisfied, then this will still be a prosecution under section 127 of the Communications Act 2003 rather than under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997. It is here that confusion is caused not just for victims, who perceive the abuse they endure very much as harassment but also generally. While evidence of harassment within the meaning of the Protection from Harassment Act forms part of the evidential assessment of whether an offence has been committed under the Communications Act, it seems that when it comes to online abuse, the legal process prefers to prosecute this as a communications crime rather than a personal one. That is to say the offence under the Communications Act uses evidence of personal attack to establish that communications channels (such as Twitter) have been abused, or in terms of the Malicious Communications Act, that communications have been malicious.

BUT this seems to pitch the crime against the communications medium rather than acknowledge the person as victim. In this sense the victim as a person is merely a vehicle for prosecuting the crime against communications medium. This seems perverse and what no doubt leaves Criado-Perez and others feeling aggrieved.

Why not prosecute the likes of Sorley and Nimmo under the Protection from Harassment Act? - section 4 of that Act sets out what amounts to putting people in fear of violence:

4.(1)A person whose course of conduct causes another to fear, on at least two occasions, that violence will be used against him is guilty of an offence if he knows or ought to know that his course of conduct will cause the other so to fear on each of those occasions.

4.(2)For the purposes of this section, the person whose course of conduct is in question ought to know that it will cause another to fear that violence will be used against him on any occasion if a reasonable person in possession of the same information would think the course of conduct would cause the other so to fear on that occasion.

4.(1)A person whose course of conduct causes another to fear, on at least two occasions, that violence will be used against him is guilty of an offence if he knows or ought to know that his course of conduct will cause the other so to fear on each of those occasions.

4.(2)For the purposes of this section, the person whose course of conduct is in question ought to know that it will cause another to fear that violence will be used against him on any occasion if a reasonable person in possession of the same information would think the course of conduct would cause the other so to fear on that occasion.

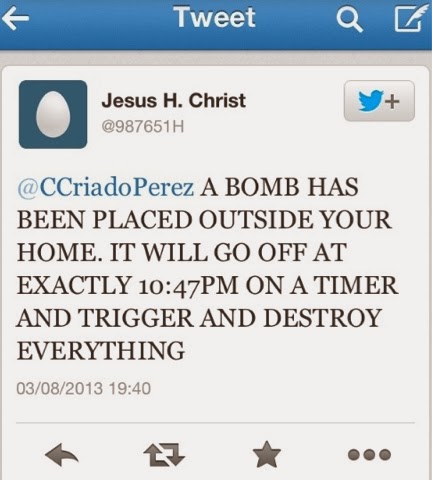

So if one looks at just a few examples of tweets sent to Criado-Perez and Stella Creasy:

...one does have to ask how these do not qualify as putting people in fear of violence and go to the offence of harassment under the Protection from Harassment Act itself.

While today's guilty plea is a step forward, the next step will be the actual sentences handed down on 24 January. The Judge did intimate that Sorley would be looking at a custodial sentence but was this as much down to the various other offences she had on the go? Meanwhile Nimmo got bail. The maximum sentence under the Communications Act is a six month prison term and/or fine. It remains to be seen what message the judge sends with his sentencing and whether that, or indeed the length of sentence under the Act iteself, i sufficient a deterrent to the ranks of trolls who abuse not just (as the law provides and protects) a communications medium but the lives and psychological welfare of real human beings.

It seems appropriate to hand over to Caroline Criado-Perez for sign off (though not forgetting Stella Creasy) also.

Thank you to those of you who have offered your support today. For obvious reasons I am staying off twitter (cont) http://t.co/GwilIHuUqn

"This is not a joyful day, these two abusers reflect a small drop in the ocean, both in terms of the abuse I received across July and August, but also in terms of the abuse that other women receive online.

"I hope that for some people who are watching, this conviction will be a warning: online abuse is not consequence-free".

No comments:

Post a Comment